Contents

- What is hematochezia?

- Difference between hematochezia and melena, hematemesis, rectorrhagia and hematopapyrus

- How the stool look and color may indicate where bleeding came from?

- What are the causes of hematochezia?

- What are the signs and symptoms of rectal bleeding and hematochezia?

- Hemorrhoids and hematochezia

- Anal fissures and hematochezia

- Polyps and hematochezia

- Diverticulosis and hematochezia

- Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and hematochezia

- Infectious colitis and hematochezia

- Cancers and hematochezia

- Angiodysplasia and hematochezia

- May hematochezia have no cause?

- Hematochezia importance for the diagnosis of underlying conditions

- Hematochezia and lower GIT bleeding management

- What shall be done in the case of massive lower GIT bleeding?

- Initial resuscitation and assessment for hematochezia

- Hematochezia and localization of bleeding site

- Initial hemostasis for hematochezia

- Vasoconstrictive therapy for hematochezia

- Therapeutic colonoscopy for hematochezia

- Superselective embolization for hematochezia

- Endoscopic therapy for hematochezia

- Surgery for massive lower GIT bleeding

What is hematochezia?

Hematochezia is a medical term for rectal bleeding. It refers to the passage of bright red blood from the rectum which is often mixed with stool or blood cloths. Hematochezia is most commonly associated with lower GIT bleeding (cecum to anus) usually from the rectum, colon, or hemorrhoids, but rarely it can be also occur as a brisk of upper gastrointestinal (stomach to ileum) bleeding or if there is an excessive bleeding.

Rectal bleeding is most usually associated with diarrhea. As a medical term hematochezia is in general population often confused and mixed up with melena and rectorrhagia, so the easiest and the most appropriate term for all may be bright red blood per rectum (BRBPR).

Hematochezia severity depends mainly on the amount and duration of bleeding. Severe cases need urgent treatment and hospitalization. In such cases the patient may be given blood transfusion in order to retain the blood volume.

Mild cases can be easily managed in the doctor office without need for hospitalization. Most cases have mild hematochezia with small blood quantities, usually occurring on the toilet papers. The main purpose in managing rectal bleeding is to support the patient circulation and then to diagnose and manage the underlying cause.

Difference between hematochezia and melena, hematemesis, rectorrhagia and hematopapyrus

As described, hematochezia is rectal bleeding most commonly associated with lower GIT bleeding (cecum to anus) and it represent as bright red sometimes fresh blood. On the other hand melena usually signifies bleeding that comes from the upper gastrointestinal tract (e.g bleeding from stomach ulcers, duodenum or from the small intestine). Bleeding in the case of melena is: black, “tarry” (sticky) and smelling because the blood stays in the gastrointestinal tract for a longer period of time before defecation.

The main difference between rectorrhagia and hematochezia is that, in the latter phase, rectorrhagia is not associated only with defecation; instead, it is also related with expulsion of fresh bright red blood without stools. However, the phrase bright red blood per rectum (BRBPR) is related with both hematochezia and rectorrhagia.

Hematopapyrus is blood on the toilet paper noticed when wiping, usually caused by hemorrhoids. It comes mostly from rectum. Blood on toilet paper may or may not be present in the case of hematochezia.

Hematemesis is a medical term for the blood vomiting, which may be noticeably red or have an look similar to coffee grounds.

How the stool look and color may indicate where bleeding came from?

Blood in the stool may be bright red, black and tarry, maroon in color or occult (not visible to the naked eye). Causes of blood in the stool may be different from harmless GIT conditions such as hemorrhoids or anal fissures and straining because of hard stools correlated with constipation to serious conditions such as cancer. If duration and amount of blood in stool is severe, it should be evaluated by a health care professional.

The color of the blood that may show up after defecation or without defecation may represent the location of the bleeding in the gastrointestinal tract. General rule is that, the closer the bleeding site is to the anus, the blood will be fresher and brighter red. Thus, bleeding from the anus, rectal region and the sigmoid colon tend to be bright red, while bleeding from the transverse colon and the right colon tend to be dark red or maroon in color.

The color of the blood in stool can also be black, smelly, and tarry and as described above it is called melena. It occurs when the blood stays enough in the colon giving the time for the bacteria to breakdown the blood into hematin chemicals which are black.

Thus, melena signifies bleeding is from the upper gastrointestinal tract. In some cases melena may also occur with bleeding localized in the right colon. Bleeding from the sigmoid colon and the rectum usually does not stay quite enough for the bacteria to turn it into black.

In some not so common cases caused by substantial bleeding from the right colon, and upper parts of the GIT such as gastric or duodenal ulcers may cause fast passage of the blood in the GIT and result with bright red rectal bleeding. This may happen because the blood is moving so rapidly that there is not enough time for the bacteria to breakdown it and to turn the blood in black.

Occasionally, GIT bleeding can be so slow to cause either melena or rectal bleeding. In such cases, bleeding is most commonly occult and is not visible to the naked eye. Blood can be only found by laboratory testing the stool for blood. Occult bleeding is in many ways as similar as rectal bleeding and may have the same symptoms as rectal bleeding. Results commonly show that occult bleeding is often associated with anemia because of the iron loss – iron deficiency anemia.

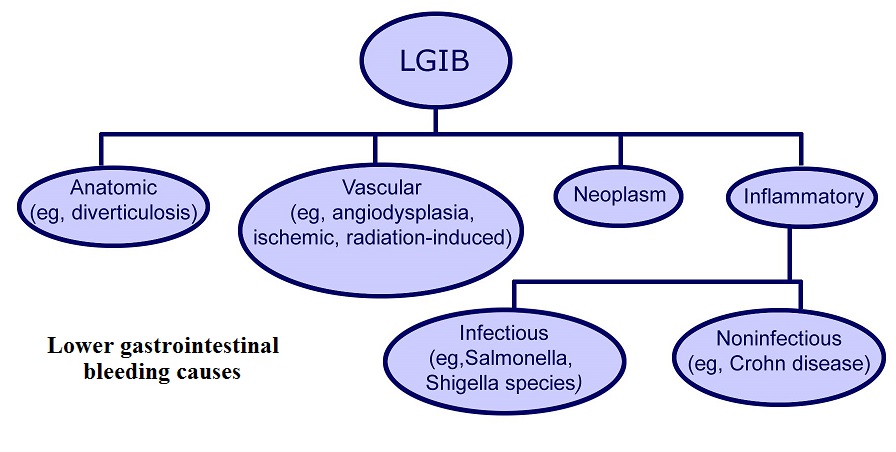

What are the causes of hematochezia?

In nearly 90% cases of hematochezia, the bleeding source lies in the colon. The amount and severity of bleeding is however variable. Hemorrhoids are known to cause only minor bleeding, whereas the conditions such as diverticular disease and vascular malformations may provoke severe and life-threatening bleeding. The other 10% of bleeding cases may be caused from location in the GIT which are above from colon.

If the bleeding is considerable from upper GI blood may be also bright and red and this may happen in cases of peptic ulcer disease, Mallory-Weiss syndrome, arteriovenous malformations, gastroesophageal varices, duodenitis, gastritis, and esophagitis.

The most common causes of hematochezia are following:

- Hemorrhoids

- Anal fissure

- Proctitis

- Polyps – Abnormal tissue growth. Bleeding can also occur after surgical resection of polyps

- Condyloma acuminata

- Diverticular Disease – blood comes from colon because of the defects in the external muscle layers

- Crohn’s disease

- Ulcerative colitis

- Ischemic colitis – Colon Inflammation caused by inadequate blood supply

- Rectal ulcer

- Rectal prolapse

- Angiodysplasia – Vascular malformations or blood vessels dialtation in the walls of intestines.

- Rectal trauma

- Anal cancer

- Colon cancer – uncommon, but very important cause

- Radiation therapy

- Idiopathic – In nearly 1/4 of cases, the source of bleeding can be identified

What are the signs and symptoms of rectal bleeding and hematochezia?

Rectal bleeding with or without hematochezia can be present with following signs and symptoms:

- Passing fresh blood

- Fresh blood on the surface of stools

- Fresh blood mixed with stool

- Fresh blood on the toilet paper

- Pink coloration of the toilet paper

- Dark colored stools; tarry stools or maroon stools

- Blood on the underwear

Various other symptoms may be related with rectal bleeding such as:

- Pain when passing blood, typically if anal fissures are present

- Sensation of bulge from the anus

- Tearing sensations before passing stools

- Cramping

- Pain in the abdomen

- Constipation

- Unintentional loss of weight

- Long straining

- Loss of appetite

- Unexplained fatigue

- Anemia

Hemorrhoids and hematochezia

Hemorrhoidal hematochezia is most usually painless, despite bleeding caused by fissures tends to be painful. Hemorrhoids are also present with strangulation and pruritus. Typically, hemorrhoids may result with red-bright blood coats in the stool at the end of defecation or blood may stay on the toilet paper. In very rare cases bleeding may be massive, distressing the patient.

Anal fissures and hematochezia

Anal fissure is painful condition where the lining of the anal canal is torn. It is usually caused by physical trauma due to constipation or because of intensive bowel movement through tight muscles of the rectum.

The bleeding amount and hematochezia that may occur with an anal fissure is mostly small and noticeable on bowl or on the toilet paper as bright red in color. The anal fissure symptoms are commonly mistaken for hemorrhoids, but it can be differentiate, because hemorrhoids generally do not cause pain with bowel movements.

Polyps and hematochezia

Polyps are irregular tissue growth on the colon wall. Polyps can cause lower GIT bleeding and hematochezia, but more frequently, bleeding will occur when polyps are surgically removed.

Diverticulosis and hematochezia

Diverticulosis develops when pouches form in the wall of the colon. About 1/3 of the patients with hematochezia have diverticular diseases. However, only 3-15% of them will have present blood in stool. Diverticular disease can be diagnosed by a colonoscopy.

There are different treatment options for this disease. If colonoscopy is able to find the bleeding site, local injection of epinephrine or electrocautery can be used for bleeding control. If these methods fail to stop bleeding or if bleeding reoccurs, surgical resection of the colon can be performed.

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and hematochezia

Colon inflammation can be caused by various conditions such as: infections, ischemia, radiotherapy, and inflammatory bowel diseases including Ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s Disease. Amongst IBD, Ulcerative Colitis is known to be more commonly present with observable hematochezia than Crohn’s disease. Crohn’s disease rarely causes hematochezia visible to the naked eye; however laboratory results may represent occult blood in patients suffering from this condition.

Infectious colitis and hematochezia

Infectious colitis commonly causes bloody diarrhea. Bacteria including Escherichia coli, Shigella, Salmonella, Clostridium difficile, Campylobacter can cause infectious colitis. Cytomegalovirus can also cause blood mixed diarrhea in patients with low immunity, especially in those with AIDS. Antibiotics use during long-term period may provoke Clostridium difficile colitis.

Radiotherapy for different abdominal and pelvic cancers can commonly cause colitis with lower GI bleeding resulting with blood in the stool. Mesenteric artery ischemia may also result in colitis, in which patient has bloody diarrhea and abdominal pain. This may require urgent surgical intervention.

Cancers and hematochezia

Patients who have colorectal cancers don’t necessarily have blood in their stools. Actually, hematochezia is rare symptom in such patients, but it is very significant as it might be the reason of poor prognosis.

Hematochezia might be the earliest and sometime the only symptom of colon cancer in its initial stages. It occurs rarely and gradually and is not usually related with pain. A colonoscopy is used as a major diagnostic procedure to rule out colorectal carcinomas. It should be known that massive bleeding can also occur in patients with colorectal cancers.

Angiodysplasia and hematochezia

Angiodysplasias is degenerative condition characterized by blood vessels dilation in the intestinal walls. This condition may cause massive bleeding occasionally with heamtochezija, which in some cases may be life threatening.

May hematochezia have no cause?

Yes, hematochezia may occur with no evident cause, and this is called idiopathic heamtochezia. In nearly 25% of the patients with blood in the stool, there is no known cause to be found. Most commonly in such cases, hematochezia is resolved spontaneously.

Hematochezia importance for the diagnosis of underlying conditions

During physical examination it is very important to mention if hematochezia is present, because in some cases this may be very important symptom for diagnosing underlying condition. Some of the following guidelines may be useful for diagnosis:

- Taking detail anamnesis including: related symptoms, onset, duration and blood amount, previous history, and family history.

- Full physical examination, especially if anemia is suspected, abdomen signs and symptoms, and rectal examination.

- Anoscopy is endoscopic procedure that can be used for the visualization of the anus and rectum. Sigmoidoscopy or colonoscopy can be also used especially if colonic abnormalities are suspected.

- Radionuclide scans may be also helpful to determine the location of the site of bleeding

- Complete blood count can be also done in order to determine the severity of anemia caused by the rectal bleeding. Serum electrolytes levelsshould be also checked.

- Coagulation profile is also recommended, including aPTT – activated partial thromboplastin time PT – prothrombin time, platelet count, and bleeding time.

- Abdomen and pelvis helical CT scanning can be used when a routine tests fails to determine the cause of active GI bleeding. This procedure is able to diagnose following: vascular extravasation of the contrast medium, thickening of the bowel wall, contrast enhancement of the bowel wall, vascular dilatations.

Patients who have experienced multiple episodes of hematochezia without a known source or diagnosis should be examined with some of following procedures:

- Elective mesenteric angiography

- Upper and lower endoscopy

- Meckel scanning

- Upper GI series with small bowel assessment

- Enteroclysis

Rare causes of lower GI bleeding that may need to be considered include the following:

- Chronic radiation enteritis/proctitis

- Small bowel diverticulosis

- Meckel diverticulum

- Ischemic colitis/mesenteric vascular insufficiency

- Colonic/rectal varices

- Portal colopathy

- Solitary rectal ulcer syndrome

- Diversion colitis

- Dieulafoy lesion of colon

- Dieulafoy lesion of small bowel

- Vasculitides

- Small bowel ulceration

- Intussusception

- Endometriosis

- GI bleeding in runners

Hematochezia and lower GIT bleeding management

The management hematochezia and lower GIT bleeding has 3 principles, as follows:

- Resuscitation and initial assessment

- Localization of the bleeding site

- Therapeutic intervention to stop bleeding at the site

Progresses in diagnostic and therapeutic angiography and endoscopy, the capability to localize and effectively treat lower GIT bleeding and hematochezia have resulted in improved patient outcomes and reduced healthcare costs. The requirement for surgery has also been meaningfully reduced.

What shall be done in the case of massive lower GIT bleeding?

Massive lower GIT bleeding can be a life-threatening condition. Initial resuscitation is one of the most important components in the management of massive bleeding. 2 large-bore intravenous (IV) catheters and isotonic crystalloid infusions should be administered in such cases.

Vital signs assessment, including monitoring of heart rate, pulse pressure, systolic blood pressure, and urine output, should be also achieved. Orthostatic hypotension treatment is also needed when blood loss is more than 1L.

Initial resuscitation and assessment for hematochezia

Initial resuscitation includes establishing large-bore IV access and management with normal saline. Besides ordering routine laboratory tests, blood should be typed and cross-matched. The volume of patient’s blood loss and hemodynamic status need to be determined and when severe bleeding is present, the patient may need invasive hemodynamic monitoring to direct therapy.

Hematochezia and localization of bleeding site

If it is not determined that bleeding comes from lower GIT, it should be considered that bleeding comes from the upper GIT. This may happen in about 10% of cases. To be sure that bleeding actually comes from lower GIT; some patients should have a nasogastric tube placed, and if the lavage or aspirate do not have any blood or coffee ground material but do have bile, then bleeding that comes from the upper GIT is unlikely. Esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) should be performed in the case of further suspicion.

Initial hemostasis for hematochezia

In hemodynamically stable patients with mild to moderate bleeding colonoscopy should be initially performed. When the bleeding site is localized, therapeutic options are injection with vasoconstrictors or sclerosing agents and coagulation.

If the bleeding is caused by diverticulosis, coagulation, epinephrine injection, and metallic clips may be used.

In the case of recurrent bleeding, the affected bowel segment should be resected.

In patients with angiodysplasia, thermal therapy including electrocoagulation or argon plasma coagulation is effective.

Vasoconstrictive therapy for hematochezia

Vasoconstrictive drugs such as vasopressin (Pitressin) are commonly used in situations with lower GIT bleeding. Vasopressin is a pituitary hormone which causes intense vasoconstriction in the splanchnic circulation reducing the blood flow and facilitates hemostatic plug formation in the bleeding vessel.

Vasopressin infusions are very effective in the case of diverticular bleeding, which is arterial. However, the efficacy is very low in patients with severe atherosclerosis and coagulopathy.

The use of epinephrine with propranolol and vasopressin has been also studied. Although epinephrine and propranolol significantly reduced mesenteric blood flow, they also produced a rebound effect increasing in blood flow and recurrent bleeding.

Therapeutic colonoscopy for hematochezia

Therapeutic colonoscopy has been proved useful in GIT bleeding induced by the radiation and in the treatment of polyp lesions. Colonoscopy treatment of radiation-induced bleeding includes topical application of formalin, laser therapy, and argon plasma coagulation. Neoplastic bleeding caused by polyps needs polypectomy. Patients diagnosed with colonic tumors may also need surgical resection.

Superselective embolization for hematochezia

The alternative for vasoconstrictive therapy is embolization with following agents: coil springs, gelatin sponge, polyvinyl alcohol, and oxidized cellulose. Embolization includes superselective catheterization of the bleeding vessel in order to minimize necrosis. It is indicated for the cases when vasopressin is unsuccessful or contraindicated.

When the bleeding location is recognized, microcoils can be used to occlude the broken vessel and to achieve hemostasis. Polyvinyl alcohol and Gelfoam can be also used alone or in combination with microcoils. In cases when terminal mural branches of the bleeding vessel cannot be catheterized, the procedure should be aborted and surgery should be performed.

Endoscopic therapy for hematochezia

Endoscopic regulation of bleeding can be attained using thermal modalities or sclerosing agents. Absolute alcohol, sodium tetradecyl sulfate and morrhuate sodium can be used for sclerotherapy of both upper and lower GIT bleeding.

Endoscopic thermal modalities including electrocoagulation, laser photocoagulation, and heater probe can also be used to stop bleeding. Endoscopic control of bleeding is appropriate for GIT polyps and cancers, endometriosis, mucosal lesions, arteriovenous malformations, postpolypectomy hemorrhage, and colonic and rectal varices. Postpolypectomy bleeding can be managed by polypectomy electrocoagulation with either snare or hot biopsy forceps or by epinephrine injection.

Surgery for massive lower GIT bleeding

Emergency surgery is needed in about 10-25% of patients with lower GIT bleeding in whom no surgical treatment was unsuccessful or unavailable. Embolization failure usually warrants surgical intervention.

Indications for surgery are:

- Persistent hemodynamic instability with active bleeding

- Persistent, recurrent bleeding

- Transfusion of more than 4 units packed red bloods cells in a 24-hour period, with active or recurrent bleeding

Factors such as comorbidity disease and individual surgical practices play an important role in deciding which patient need surgery.

Segmental bowel resection with precise localization of the place of bleeding is a well-accepted surgical procedure in hemodynamically stable patients. Subtotal colectomy is another procedure of choice in individuals who are persistently bleeding from an unknown cause. 2008 SIGN guideline recommends subtotal colectomy for the management of colonic bleeding that is uncontrolled by other procedures.

Intraoperative esophagogastroduodenoscopy, colonoscopy and surgeon-guided enteroscopy can be helpful in diagnosing undiagnosed massive GI bleeding. Depending on the patient’s condition and availability of recourses, it may be in some cases be better to perform subtotal colectomy with distal ileal inspection.

Hemodynamically stable patients need preoperative localization of the hemorrhage site, while hemodynamically unstable patients with active bleeding may undergo emergency laparotomy with intraoperative endoscopy. Once the bleeding site is preoperatively localized, vasopressin infusion should be used as a temporizing measure to reduce the bleeding before patients undergo segmental colectomy.

“Where does your foot hurt with plantar fasciitis? How do you prevent plantar fasciitis?“