Contents

- What is psilocybin?

- Psilocybin pronunciation

- The chemistry of psilocybin

- Physiochemical properties of psilocybin and psilocyn

- What are street names for psilocybin?

- Psilocybin history of use

- Which mushrooms contain the highest amounts of psilocybin? Where they can be found?

- Why do people use psilocybin?

- Psilocybin mechanism of action

- When psilocybin starts to work? How long does effect last?

- Psilocybin vs. LSD effects

- Effects of psilocybin use

- Psilocybin dose-effects

- Psilocybin drug experiences

- How is psilocybin most commonly used/abused?

- Why is psilocybin used infrequently?

- Psilocybin abuse, dependence, withdrawal and tolerance

- Psilocybin detection tests

- Can urine drugs test screens detect psilocybin?

- How long do psilocybin stay in your system?

- Abnormalities during psilocybin use

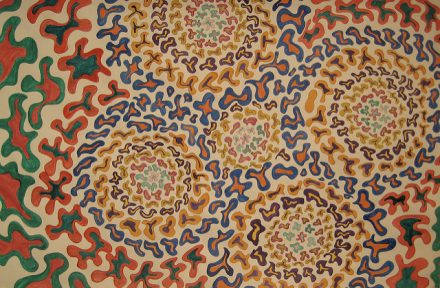

- Psilocybin and hallucinations

- Psilocybin intoxication treatment

- Is psilocybin legal in the U.S.?

- Psilocybin medical use for “existential distress” in cancer patients

- Effects of psilocybin in major depressive disorder (ongoing study)

- Psilocybin for treatment of obsessive compulsive disorder (ongoing study)

- Psilocybin-assisted treatment for alcohol dependence (ongoing study)

- Psilocybin-facilitated treatment for cocaine use (ongoing study)

- Psilocybin for the treatment of cluster headaches (ongoing study)

- Psilocybin-assisted psychotherapy for anxiety in people with stage IV melanoma (ongoing study)

What is psilocybin?

Psilocybin (4-phosphoryloxy-N,N-dimethyltryptamine) is a naturally occurring psychedelic prodrug substance produced by more than 200 species of mushrooms, which are collectively known as psilocybin mushrooms, indigenous to tropical and subtropical regions of Mexico, South America and the United States. These mushrooms usually contain less than 0.5 % psilocybin plus trace amounts of psilocin, another hallucinogenic substance. After ingestion, psilocybin is metabolized into psilocin, which is the primary active chemical.

There are more than 180 species of mushrooms that contain the chemicals psilocybin or psilocin. Like the peyote, hallucinogenic mushrooms have been used in native rites for centuries. Both psilocybin and psilocin can also be produced synthetically in the lab. There have been reports that psilocybin bought on the streets can actually be other species of mushrooms laced with LSD.

Psilocybin pronunciation

Psilocybin is pronounced as: seye-loh-SEYE-bin (also pronounced seye-loh-SIB-in)

The chemistry of psilocybin

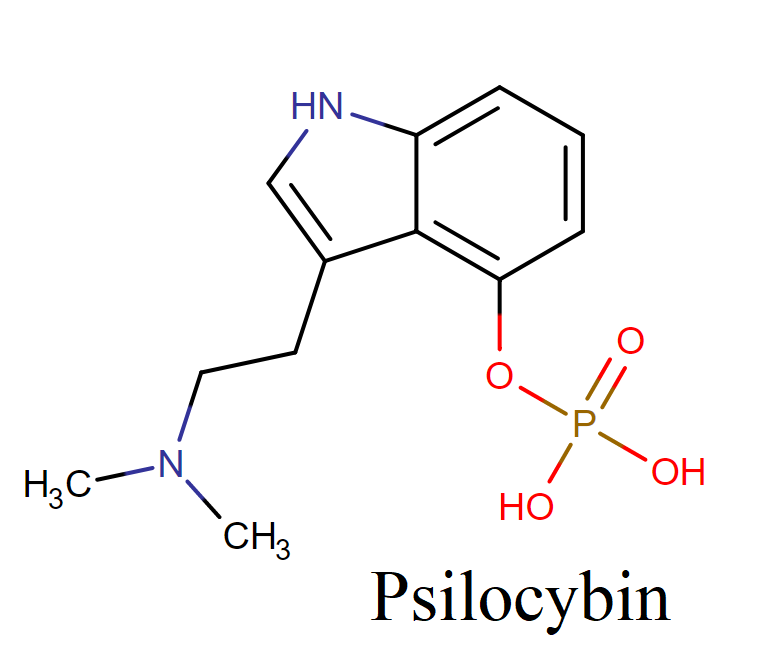

This molecule belongs to the class of organic compounds known as tryptamines and derivatives. These are compounds containing the tryptamine backbone, which is structurally characterized by an indole ring substituted at the 3-position by an ethanamine. Psilocybin and psilocin are structurally similar to tryptamines (bufotenine, harmine, LSD)

IUPAC name: [3-[2-(dimethylamino)ethyl]-1H-indol-4-yl] dihydrogen phosphate

Structure:

Physiochemical properties of psilocybin and psilocyn

Psilocybin is soluble in methanol and aqueous ethanol, but relatively insoluble in petroleum ether and chloroform. The rapid dephosphorylation of psilocybin to psilocin suggests that psilocybin is a profrug.

In equimolar amounts, psilocybin and psilocin produce similar hallucinogenic effects, but psilocin is approximately 1 ½ times more potent hallucinogen than psilocybin. The demethylated psilocybin compounds (baeocystin, norbaeocystin) are serotonin analogues that occur in some Psilocybe species.

Psilocybin is colorless, and the incubation of this compound with ceruloplasmin does not cause the uptake of oxygen or the formation of a blue color. Psilocin lacks the stabilizing phosphate group. The oxidation of this compound or the addition of ceruloplasmin or copper oxidase from the gill plates of Mytilus edulis (blue mussel) produces strongly blue – colored products.

What are street names for psilocybin?

The most common street names for psilocybin are: Blue Caps, Boomer, Buttons, God’s Flesh, Hombrecitos, Las Mujercitas, Liberty Caps, Little Smoke, Magic Mushroom, Mexican Mushrooms, Mushies, Mushrooms, Mushroom Soup, Mushroom Tea, Musk, Pizza Toppings, Rooms, Sacred Mushroom, Shrooms, Silly Putty, Simple Simon, Teonanacatl.

Psilocybin history of use

The Aztecs and neighboring tribes used ceremonial mushrooms called teonanácatl (God’s flesh) in religious rites before the arrival of the Spaniards in the New World. Medieval Spanish books from the 16th and 17th centuries mentioned the use of small gill fungi (teonanácatl) by North American Indians for ritual and medicinal purposes.

Small stone statues of fungi from ancient Mayan ruins in Guatemala suggest the use of hallucinogenic mushrooms before the time of Christ. The use of mushrooms by North American Indians to produce mystical revelations during religious ceremonies continued into the 20th century.

In the late 1950s, Wasson rediscovered the mushroom cult in Southern Mexico. Psilocybe mexicana R. Heim was identified as the active component of teonanácatl; subsequently, Heim et al provided botanical descriptions of several species of hallucinogenic Psilocybe fungi. In 1958, Hofmann et al isolated 2 hallucinogenic components (i.e., psilocybin, psilocin) from mushrooms used in Mazatec Indian ceremonies in the state of Oaxaca, Mexico.

These indole compounds have LSD – like properties and produce alterations of autonomic function, motor reflexes, behavior, and perception. Hoffer and Osmond elucidated the chemical structures of psilocybin and psilocin in 1967.

In the 1960s, recreational ingestion of psilocybin – containing mushrooms was popularized in the western United States by Aldous Huxley and Carlos Castaneda. Later, recreational use of these substances spread to Australia followed by the United Kingdom and then to the rest of Europe. In the late 1990s, hallucinogen use (mescaline, psilocybin) increased significantly in high school students.

Which mushrooms contain the highest amounts of psilocybin? Where they can be found?

The three most important genera of mushrooms containing psilocybin are Psilocybe, Panaeolus, and Gymnopilus. The best – known European psychoactive fungi is Psilocybe semilanceata, whereas the most common hallucinogenic mushroom in the United States is Psilocybe cubensis and, to a lesser extent, Psilocybe stuntzii and Panaeolus subbalteatus.

The principal hallucinogenic mushrooms in North America grow primarily in the Pacific Northwest, Hawaii, Texas, and Florida, usually on animal manure in pastures and grain fields.

Psychoactive mushrooms in the Hawaiian Islands that contain psilocybin include Copelandia anomala, Copelandia bispora, Copelandia cambodginiensis, Copelandia cyanescens, Copelandia tropicalis and Panaeolus subbalteatus. The use of fungi as a psychoactive agent is uncommon in South America and Asia. Wavy caps refer to Psilocybe cyanescens.

Psilocybe baeocystis and Psilocybe semilanceata contain the demethylated psilocybin compounds, baeocystin and norbaeocystin. Specimens from other Psilocybe species [ P. cyanescens, P. cubensis, P. pelliculosa, P. sylvatica , P. stuntzii) and genera (Conocybe smithii Watling, Panaeolus subbalteatus ] usually contain smaller concentrations of baeocystin.

Why do people use psilocybin?

For some persons a psilocybin session is a spiritual encounter. Euphoria, self-examination, and meditation about the meaning of life can occur after taking the drug. Along with vivid hallucinations, changes might occur in perception of time and space, and people may feel detached from their bodies or imagine that their bodies are changing shape.

As with many other drugs of abuse, scientists find that a user’s personality can make a huge difference in what happens with psilocybin; some persons can prevent any hallucinogenic effects at all.

Personality may influence physical actions of the drug as well; in one experiment volunteers with less-stable personalities needed less light than usual in order to view reproductions of artwork; volunteers who were more normal needed more light than usual.

An experiment found the drug’s psychic effects to be stronger on schizophrenics. Experiences can be so extraordinary that some investigators have wondered if the drug can evoke ESP (extrasensory perception) abilities.

One of the most famous scientific studies with psilocybin was conducted by Dr. Timothy Leary before he became a counterculture icon. Leary and his researchers ingested the drug together with state prison inmates to determine whether the experiences would promote life changes motivating inmates to stay out of prison upon release.

Leary reported outstanding success, with psilocybin inmates committing far fewer repeat offenses sending them back to prison. Subsequent investigation, however, revealed serious flaws in Leary’s research; in reality the percentage of inmates returning to prison for new crime was the same in the psilocybin group as in those who did not receive the drug.

Leary’s advocacy of widespread hallucinogenic drug use was based partly upon flawed research. A case report notes successful use of psilocybin mushrooms to ease, though not eliminate, compulsions and obsessions.

Psilocybin mechanism of action

In the body, psilocybin is rapidly dephosphorylated into psilocin, which is an active form of compound that works a partial agonist for serotonin (5-HT) receptors. Psilocin has a high affinity for the 5-HT2B and 5-HT2C receptors in the human brain, with a slightly lower affinity for the 5-HT2A receptor. Psilocin has a low affinity to 5-HT1 receptors, including 5-HT1A and 5-HT1D.

These receptors are located in various parts of the brain, including the cerebral cortex, and are involved in a wide range of functions, including motivation and regulation of mood. The psychotomimetic (psychosis-mimicking) effects of psilocin can be blocked in a dose-dependent fashion by the 5-HT2A antagonist drug ketanserin.

Different evidences have shown that interactions with non-5-HT2 receptors also contribute to the subjective and behavioral effects of the drug. In the basal ganglia, psilocin may indirectly increase the concentration of dopamine.

Additionally, some psychotomimetic symptoms of psilocin are reduced by haloperidol, a non-selective dopamine receptor antagonist. Taken together, these suggest that there may be an indirect dopaminergic contribution to psilocin’s psychotomimetic effects.

Unlike LSD, which binds to D2-like dopamine receptors in addition to having strong affinity for several 5-HT receptors, psilocybin and psilocin have no affinity for the dopamine D2 receptors.

When psilocybin starts to work? How long does effect last?

A short latent period of ∼ 30 – 60 minutes precedes the onset of somatic symptoms (facial erythema, mydriasis, headache, tremor, diaphoresis, agitation, euphoria). The onset of clinical effects after the ingestion of water extracts (soup, tea) is more rapid compared with the whole mushroom (i.e., about 10 minutes vs. ∼ 20 – 40 minutes, respectively).

Adverse psychologic reactions during psilocybin intoxication include depersonalization, derealization, dysphoria, disorientation, agitation, delirium, and aggressive behavior. Most symptoms resolve within 4 – 6 hours with some sleep disturbances lasting up to 24 hours; the persistence of dysphoric symptoms beyond 12 hours is rare.

Adverse psychiatric symptoms do not usually persist, although some case series report the recurrence of flashbacks and panic attacks within the first 4 months after ingestion.

Psilocybin vs. LSD effects

Compared with LSD, the ingestion of psilocybin frequently produces less intensive depersonalization, milder somatic symptoms, and more intense spatial illusions

Effects of psilocybin use

Psilocybin effects are very similar to those of other hallucinogens, such as mescaline from peyote or LSD. The psychological effects of psilocybin use most commonly include visual and auditory hallucinations and an inability to discern fantasy from reality. Panic reactions and psychosis also may occur, particularly if large doses of psilocybin are ingested.

Hallucinogens that interfere with the action of the brain chemical serotonin may alter:

- mood

- sensory perception

- sleep

- hunger

- body temperature

- sexual behavior

- muscle control

Physical effects of psychedelic mushrooms may include a feeling of nausea, vomiting, muscle weakness, confusion, and a lack of coordination. Combined use with other substances, such as alcohol and marijuana can heighten, or worsen all of these effects.

Other effects of hallucinogenic drugs can include:

- intensified feelings and sensory experiences

- changes in sense of time (for example, time passing by slowly)

- increased blood pressure, breathing rate, or body temperature

- loss of appetite

- dry mouth

- sleep problems

- mixed senses (such as “seeing” sounds or “hearing” colors)

- spiritual experiences

- feelings of relaxation or detachment from self/environment

- uncoordinated movements

- lowered inhibition

- excessive sweating

- panic

- paranoia – extreme and unreasonable distrust of others

- psychosis – disordered thinking detached from reality

If used in higher doses, including an overdose, psilocybin can lead to intense hallucinogenic effects over a longer period of time. An intense “trip” episode may occur manifesting as panic, paranoia, psychosis, frightful visualizations (“bad trip”), and very rarely death.

Abuse of psilocybin mushrooms could also lead to toxicity or death if a poisonous mushroom is incorrectly thought to be a psilocybin mushroom and ingested. If vomiting, diarrhea, or stomach cramps begin several hours after consuming the mushrooms, the possibility of poisoning with toxic mushrooms should be considered.

Tolerance to the use of psilocybin has ben reported, which means a person needs an increasing larger dose to get the same hallucinogenic effect. “Flashbacks”, similar to those occur in some people after using LSD, have also been reported with mushrooms.

Psilocybin dose-effects

The typical recreational dose of psilocybin required to produce desired effects is approximately 5 – 15 mg with a threshold of about 0.040 mg psilocybin/kg body weight and a range up to approximately 50 mg or 3.5 – 5 g dry weight (35 – 50 g, wet weight), depending on the species and psilocybin content.

In volunteer studies, the ingestion of 0.25 mg psilocybin/kg produced euphoria, sense of grandiosity, visual illusions, difficulty thinking, and impaired functioning. 44 In an double – blind experimental study of 12 volunteers receiving up to 0.25 mg/ kg psilocybin (high dose condition), reductions occurred in the speed of voluntary movements and working memory along with feelings of depersonalization and derealization.

In a clinical trial of the efficacy of psilocybin in the treatment of 9 patients with obsessive – compulsive disorder, psilocybin doses ranged up to 0.30 mg/kg. Other than transient mild hypertension in one subject, no adverse effects were reported.

The ingestion of psilocybin causes wide variation in the clinical response of different individuals ingesting the same dose. Agitation and hallucination developed after the ingestion of 10 mushrooms by one patient, whereas the ingestion of 200 mushrooms by an unrelated patient produced only abdominal pain.

The low concentration of active ingredients in these species limits symptoms after the ingestion of 1 – 2 mushrooms; relatively large numbers of mushrooms (10 – 100) are necessary to produce psychomimetic effects depending on the mood, tolerance, setting, and personality of the patient.

A case report associated the development of coma, convulsions, and hyperthermia with the ingestion of cooked mushrooms by young children, but there was no laboratory confirmation or quantitation of psilocybin; the clinical course was poorly documented.

Psilocybin drug experiences

Blood pressure rose in volunteers who received psilocybin; reaction times slowed; hearing became more sensitive; and individuals often felt cold. Dizziness, nausea, and vomiting can occur. Some persons feel nervous and even fearful during a psilocybin experience. After a psilocybin session people may feel worn out for several hours, maybe for more than a day.

Reliable information on mushroom effects is more challenging to obtain than reliable information about psilocybin because mushrooms contain many other chemicals, sometimes including illicit substances that have been added without a user’s knowledge. And mushroom eaters may simultaneously use other substances deliberately, further clouding knowledge of what the mushroom itself is doing.

With the mushrooms, burning or prickling sensations are routine, as are perspiration, yawning, fatigue, slowed pulse rate, lowered blood pressure and body temperature, and uneasiness. An overdose commonly brings on nausea, vomiting, high blood pressure, and abnormal heartbeat. Heart attack has been reported but seems uncommon.

How is psilocybin most commonly used/abused?

Mushrooms containing psilocybin are available fresh or dried and are typically taken orally. Psilocybin (4-phosphoryloxyN,N-dimethyltryptamine) and its biologically active form, psilocin (4-hydroxy-N,N-dimethyltryptamine), cannot be inactivated by cooking or freezing preparations. Thus, they may also be brewed as a tea or added to other foods to mask their bitter flavor. The effects of psilocybin, which appear within 20 minutes of ingestion, last approximately 6 hours.

Desirable effects of hallucinogenic (magic) mushroom use include feelings of a different perspective, hallucination, joviality, and a sense of being part of the natural surroundings.

In a Swedish study of 103 suspected cases of intoxication from psychoactive plants, analysis of urine samples indicated that psilocin was the most frequently detected drug, accounting for 54% of the cases. The source of psilocin for a majority of these individuals was the purchase of hallucinogenic mushrooms over the Internet.

Why is psilocybin used infrequently?

Use of these mushrooms is relatively infrequent, but the experience is often intense. In a self – selected convenience sample of hallucinogenic mushroom users in Edinburgh and Bristol, 47% of the users reported the ingestion of hallucinogenic mushrooms 4 – 12 times yearly. Reasons for the infrequent use included the intensity of the experience, anxiety, and paranoia.

This study was completed prior to the reclassification of hallucinogenic mushrooms to UK Class A drug (most harm, greatest penalty) in 2005. A cross – sectional survey of dance drug users in the UK prior to the reclassification of psilocybin indicated a lifetime (i.e., ever) and current use (i.e., within last month) prevalence of 48% and 13.7%, respectively.

Psilocybin abuse, dependence, withdrawal and tolerance

Compared to other drugs of abuse, long-term psilocybin use has not been shown to cause physical dependence or withdrawal symptoms. However, chronic users may develop tolerance, which means that they require increased doses of psilocybin in order to achieve the level of intoxication they are seeking. Additional research is needed to determine the addictive potential of psychedelic substances, such as psilocybin.

Psilocybin detection tests

Analytic methods for the detection of psilocybin and the less stable metabolite, psilocin, include infrared spectroscopy, ultraviolet spectrophotometry, thin layer chromatography, capillary electrophoresis, GC/ MS, liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry, and high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC).

Limitations of gas chromatographic methods result from the poor volatility of psilocybin and decomposition of psilocybin (i.e., heat – induced loss of phosphate group) during the injection phase; therefore, liquid chromatographic methods are preferred to separation by gas chromatography.

The presence of a phosphate ester in psilocybin limits the detection of this compound, but not psilocin by GC/MS. HPLC is the most common analytic technique with detection modes including ultraviolet, fluorescence, electrochemical, voltametric, mass spectrometry, and chemiluminescence. The limit of detection (LOD) for HPLC ranges from 1.2 × 10 – 8 mol/L (chemiluminescence) to 9.7 × 10 – 6 mol/L(fluorescence).

Other tests for damaged or decomposed samples containing psilocybin include DNA – based testing using amplified fragment length polymorphism. The one – step methanol extraction is a simple, efficient method for removing psilocybin and related compounds from a fungal mass.

Can urine drugs test screens detect psilocybin?

Although urine drugs of abuse screens do not specifically analyze specimens for psilocybin, occasionally urine drug tests are positive for amphetamine following the use of hallucinogenic mushrooms. Anecdotal reports suggest that some polyclonal antibody assay kits detect the consumption of some hallucinogenic mushrooms as positive for the presence of amphetamine. Analysis of urine from the false – positive tests for amphetamine suggested that the presence of phenethylamine account for the false – positive tests.

How long do psilocybin stay in your system?

Common hallucinogens are not detected by standard drugs-of-abuse screens. If desired by legal authorities or medical personnel, it is possible to perform laboratory assays that can detect any drug or metabolite, including psilocybin, via advanced techniques.

When tested via urine, the psilocybin mushroom metabolite psilocin can stay in your system for up to 3 days. However, metabolic rate, age, weight, age, medical conditions, drug tolerance, other drugs or medications used, and urine pH of each individual may affect actual detection periods.

Abnormalities during psilocybin use

Rare case reports document mild elevations of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), serum aspartate aminotransferase, and alkaline phosphatase following the ingestion and intravenous administration of psilocybin – containing mushrooms, but liver function is usually normal.

Following the ingestion of psilocybin, cerebral metabolic patterns as determined by fluorodeoxyglucose – PET scanning demonstrated hypermetabolism in the prefrontal and inferior temporal regions of the right hemisphere (e.g., anterior cingulate) and relatively hypometabolism in the subcortical regions (e.g., thalamus) when compared with placebo. These findings are similar to the hypermetabolism in the frontal regions associated with the ingestion of mescaline.

Psilocybin and hallucinations

Hallucinations are illusions that the afflicted person believes are real, and these distorted perceptions cause changes in emotions and behavior. Unregulated agonist activity of neurons associated with the processing of visual and emotional information produces hallucination without alteration of state of consciousness.

Psilocybin induces states of consciousness similar to acute schizophrenic disorders along with deficits in sustained and spatial attention. 58 The sense of the passage of time is slowed, resulting in a subjective overestimation of time intervals. Auditory hallucinations occur very rarely, although a heightened awareness of sound and paresthesias do develop during psilocybin intoxication.

Psilocybin intoxication treatment

Most patients ingest psilocybin – containing mushrooms without developing symptoms requiring emergency medical care. Decontamination measures are usually unnecessary; the use of decontamination measures should be limited to cases where other toxic drugs or compounds have been ingested within 1 – 2 hours of presentation. There are no specific data on the efficacy of decontamination measures (e.g., activated charcoal) after the ingestion of hallucinogenic mushrooms.

Rarely, the ingestion of hallucinogenic compounds is associated with hyperthermia that requires undressing the patient and rapid cooling measures. Dysphoria is the major complaint for most patients presenting to the emergency department after ingesting hallucinogenic mushrooms; a quiet, supportive environment (darkened room with familiar faces) along with calm reassurance usually provides sufficient treatment for the dysphoria.

The patient should be observed until the dysphoria resolves (i.e., usually within 4 – 6 h). The treatment room should contain minimal visual and auditory stimuli, and the presence of relatives or friends to give reassurance is helpful. Benzodiazepines (e.g., diazepam, lorazepam, midazolam) may be necessary for sedation if dysphoria persists.

Antipsychotics (e.g., haloperidol) should be reserved for frank hallucinations. Severely agitated patients should be evaluated for rhabdomyolysis if the agitation persists, and the possibility of Amanita phalloides poisoning should be considered in patients presenting with the late onset (e.g., > 6 h postingestion) of gastrointestinal symptoms.

Is psilocybin legal in the U.S.?

Psilocybin is a Schedule I substance under the DEA’s Controlled Substances Act, which means that it has a high potential for abuse, no currently accepted medical use in treatment in the U.S., and a lack of accepted safety for use under medical supervision.

Currently, psilocybin is not available to doctors in the clinical setting because it is listed as a Schedule I drug by the US DEA. Researchers for the study were only able to get access to the illegal compound for the study through special waivers from the U.S. FDA Other drugs found in Schedule I include marijuana, LSD, and heroin. In order for psilocybin to be prescribed for patients, it would have to be reclassified as a Schedule II medication, meaning it has a currently accepted medical use, but with severe restrictions due to addiction potential

The following are statistics related to teen hallucinogen use, in general:

- In 2014, approximately 136,000 adolescents between the ages of 12 to 17 (.5% of this population) reported being current users of hallucinogens.

- Young people with a co-occurring major depressive disorder were more likely to use hallucinogenic drugs than young people without major depression.

Psilocybin medical use for “existential distress” in cancer patients

Although it has been used for centuries, modern medicine has recently reported psilocybin uses, as well. Newest studies reported that psilocybin can reverse the feeling of “existential distress” that patients often feel after being treated for cancer. Cancer can make patients with this type of psychiatric disorder, feeling that life has no meaning.

Studies showed that typical treatments such as antidepressants are usually not effective. However, use of a single dose of synthetic psilocybin reversed the distress felt by the patients and was a long-term effect. Some advanced cancer patients described the effect from the drug as if “the cloud of doom seemed to lift.

Effects of psilocybin in major depressive disorder (ongoing study)

The proposed pilot study will assess whether people with major depressive disorder experience psychological and behavioral benefits and/or harms from psilocybin.

This study will investigate acute and persisting effects of psilocybin on depressive symptoms and other moods, attitudes, and behaviors. The primary hypothesis is that psilocybin will lead to rapid and sustained antidepressant response, as measured with standard depression rating scales.

Psilocybin for treatment of obsessive compulsive disorder (ongoing study)

This study will evaluate whether psilocybin, a hallucinogenic drug, improves symptoms of obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD), whether it is safely tolerated as treatment of OCD, and will investigate the mechanisms by which it works.

Psilocybin-assisted treatment for alcohol dependence (ongoing study)

Several lines of evidence suggest that classic hallucinogens such as psilocybin can facilitate behavior change in addictions such as alcohol dependence. The proposed investigation is a multi-site, double-blind active-controlled trial (n = 180, 90 per group) contrasting the acute and persisting effects of psilocybin to those of diphenhydramine in the context of outpatient alcoholism treatment.

Psilocybin-facilitated treatment for cocaine use (ongoing study)

The primary purpose of this study is to evaluate the feasibility and estimate the efficacy of psilocybin-facilitated treatment for cocaine use. The impact of psilocybin-facilitated treatment on the use of other drugs and outcomes relevant to cocaine involvement (e.g., criminal involvement) will be monitored.

Psilocybin for the treatment of cluster headaches (ongoing study)

The purpose of this study is to investigate the effects of an oral psilocybin pulse regimen in cluster headache. Subjects will be randomized to receive oral placebo, low dose psilocybin, or high dose psilocybin in three experimental sessions, each separated by 5 days. Subjects will maintain a headache diary prior to, during, and after the pulse regimen in order to document headache frequency and intensity before, during, and after the pulse regimen.

Psilocybin-assisted psychotherapy for anxiety in people with stage IV melanoma (ongoing study)

This study is to find out about whether two sessions of psilocybin-assisted psychotherapy are safe and will help people who are anxious as a result of having stage IV melanoma and will involve two sessions of psychotherapy combined with either 4 or 25 mg psilocybin.

The study will measure anxiety, depression, quality of life and spirituality before and after psilocybin-assisted psychotherapy, natural killer cells (a type of immune cell) will be counted from blood samples taken the day after psilocybin-assisted psychotherapy, and people will keep daily diaries reporting on how anxious they feel for each day in the study.

“Is a naproxen a controlled substance? Can naproxen get you high if snorted?“